Section 1 Economic Output

Ireland’s economic outlook remains positive, but global headwinds persist.

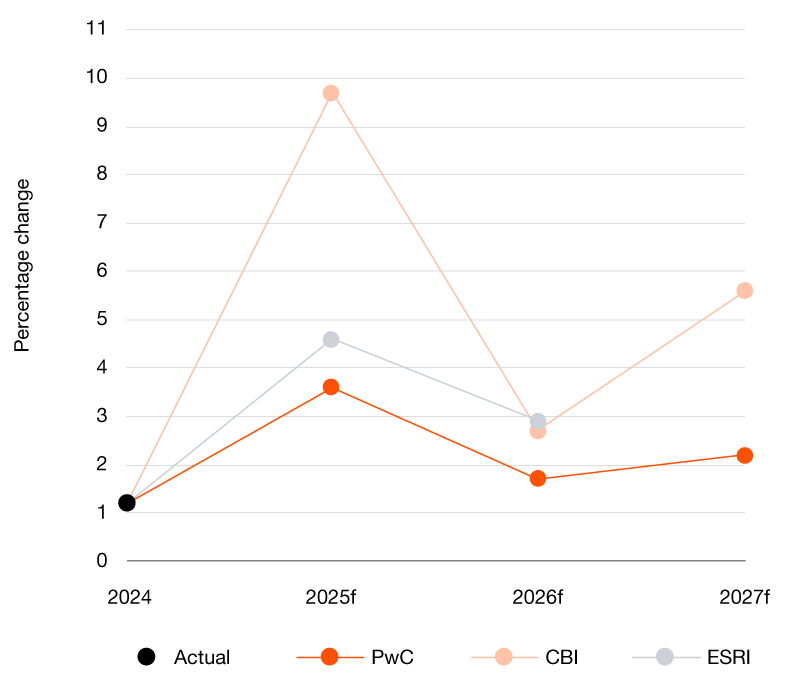

Ireland’s economic output is projected to grow steadily, though at a slightly moderated pace compared to earlier expectations. Following a 1.2% expansion in GDP in 2024, we forecast growth of 3.6% in 2025 (see Figure 1). Notably, the Central Bank of Ireland (CBI) projects GDP growth of 9.7% over the same period, driven by a surge in exports in the first half of the year. Looking ahead, we expect GDP growth to ease to around 1.7% in 2026, with the divergence in forecasts highlighting the uncertain external environment.

Export performance continues to drive growth, particularly in the pharmaceutical sector. However, risks remain elevated due to ongoing trade tensions and potential changes in international tariff regimes. The CBI’s bullish outlook for 2025 stems from strong export momentum, but this may soften if geopolitical frictions escalate further. We’re seeing more negative expectations for the profitability of MNEs across pharma, med-tech and ICT manufacturing operating in Ireland in light of the shifting US policy stance

Figure 1. GDP growth forecasts

Source: PwC, CBI, CSO, ESRI

Domestic demand remains resilient, though sentiment is softening.

Modified domestic demand (MDD), which more accurately reflects Ireland’s domestic economic activity, grew by 2.7% in 2024. A slight moderation is forecast for 2025, with projected growth of around 2.2%, followed by 2.5% in 2026 and 2.2% in 2027 (see Figure 2).

Household consumption remains the primary engine of MDD growth, supported by our robust labour market and wage growth. Consumer sentiment has been trending downward over the past two years. After a sharp drop in March 2025 to 67.5, and again in April to 58.7, the index partially recovered, reaching 62.5 in June before falling again to 59.1 in July (see Figure 3). Lower consumer confidence may weigh on discretionary spending in the coming months, particularly if global uncertainty around trade policy doesn’t dissipate.

Figure 2. MDD growth forecasts

Source: CBI, CSO, ESRI

Figure 3. Irish consumer sentiment

Source: Irish League of Credit Unions

Global economic conditions remain subdued amid persistent uncertainty.

Our open and export-oriented economy continues to face headwinds from a challenging global environment. We project the US economy, which expanded by 2.8% in 2024, to moderate to 1.6% growth in 2025. We expect a 1.6% growth rate again in 2026, before increasing to 2.3% in 2027 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Global GDP growth forecasts

Source: PwC, Eurostat, BEA, ONS

Growth in the euro area remains modest, with GDP expected to rise by 0.8% in 2025, and gradually strengthening to 1.5% by 2027. The UK economy also saw a modest recovery in 2024, growing by 1.1%, with forecasts pointing to a steady but subdued expansion of 1.0% in 2025, 1.2% in 2026, and 1.7% by 2027. These moderate global growth prospects, combined with ongoing geopolitical tensions, continue to pose risks to Ireland’s economic outlook. While domestic demand remains stable, the external environment underscores the importance of maintaining our competitiveness and diversifying export markets to support sustainable growth.

Section 2 Inflation

Ireland’s inflation outlook remains broadly stable, with updated forecasts indicating inflation is likely to remain close to target levels over the medium term.

We project inflation of 2.0% in 2025, moderating to 1.9% in 2026 and 1.6% in 2027 (see Figure 5). The CBI forecasts a similar trajectory, with inflation easing from 1.9% in 2025 to 1.7% by 2027. Meanwhile, the ESRI anticipates a slightly more persistent inflationary trend, projecting 2.0% in 2025 and a modest uptick to 2.1% in 2026.

While headline inflation continues to decline, the services sector remains a key source of upward pressure, particularly driven by strong consumer demand in hospitality, including restaurants and cafes. This suggests that while inflation is broadly under control, sector-specific dynamics may sustain price pressures in the near term.

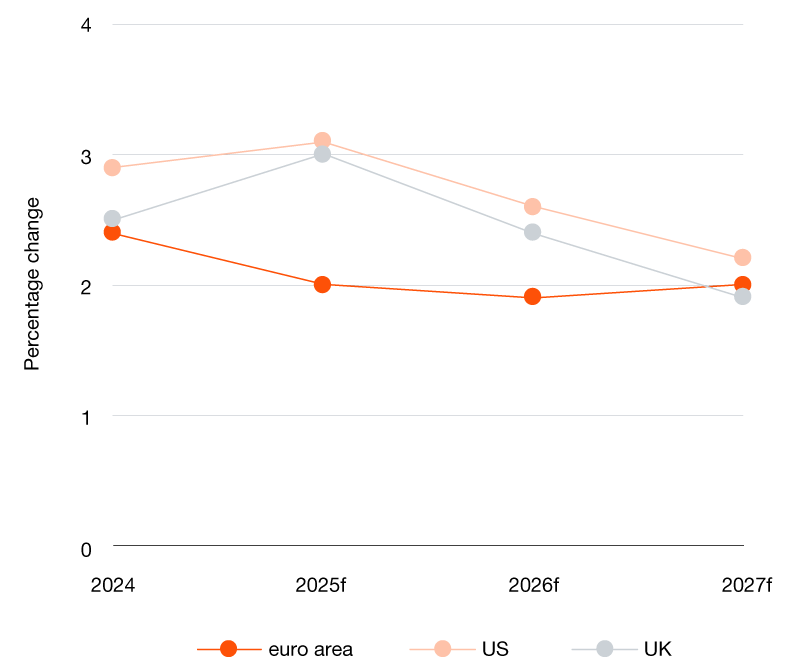

Inflation projections for Ireland’s main trading partners remain on a downward path, though regional differences persist.

We expect inflation to continue moderating across the euro area, the US and the UK over the forecast horizon (see Figure 6). Our latest projections suggest inflation will range from 2% to 3.1% across the three economies shown in 2025, with a gradual decline towards the 2% target by 2027. We forecast euro area inflation to remain stable at 2.0% from 2025 to 2027, while US inflation is expected to ease from 3.1% in 2025 to 2.2% in 2027. We project UK inflation to fall more sharply, from 2.3% in 2025 to below target at 1.9% in 2027.

While the overall trend remains downward, the pace of annual decreases varies across regions, reflecting differing monetary policy stances and domestic economic conditions. The inflationary impact of recent trade policy developments, particularly in the US, remains a key source of uncertainty with potential implications for global supply chains and demand dynamics. Indeed, July inflation reports recorded increases in inflation in the US and UK. Despite the increase in inflation, the Federal Reserve has come under increasing pressure to decrease interest rates from the US administration.

Figure 5. Inflation forecasts for Ireland

Source: PwC, CBI, CSO, ESRI

Figure 6. Global inflation forecasts

Source: PwC

Section 3 Labour Market

The monthly unemployment rate was 4.9% in July, up from 4.6% in June.

Despite growing economic uncertainty globally, Ireland’s job market is proving resilient, with only a slight increase in the seasonably adjusted unemployment rate in July. Uncertainty, where it persists, is likely to weigh on investment and hiring decisions, however. The youth unemployment rate is significantly higher than that of the whole economy, with a 12.2% rate for the 15–24-year-old cohort, up from 11.3% in June. Young people are overrepresented in the unemployment statistics, and this has been a persistent pattern since the early 2000s.

We need targeted initiatives to give young people the opportunity to retrain. This would not only help reduce youth unemployment but would also go some way to relieving the skills shortages currently constraining output — not least in the construction sector, as we discuss below.

While Ireland’s construction workforce has been growing rapidly, it remains below Celtic Tiger levels and represents a smaller share of overall employment.

We have over 57,000 fewer construction workers in Ireland today compared to 2007. This is despite the total number of people working in Ireland’s economy increasing by over 600,000 over the same period. The result is that construction’s share of the labour market has fallen from 10.9% to 6.4% since 2007. This has significant consequences as we work to close our substantial infrastructure deficit and address a prolonged housing crisis.

We’re growing increasingly concerned about the potential impact on Ireland’s global competitiveness at a time of great economic uncertainty. We look at trends in Ireland’s construction labour market below.

Figure 7. Number of workers and vacancies in the construction sector

Source: CSO

Figure 8. Construction apprenticeship and work permit numbers

Source: NAO, DETE

Construction employment in Ireland has risen since the COVID-19 pandemic, but job vacancies have also grown.

Over the past five years, our construction sector has experienced a notable expansion in its workforce, with employment rising from 126,800 in Q1 2021 to 181,500 in Q1 2025 — a robust increase of 43% (see Figure 7). This growth indicates strong demand within the sector, driven by ongoing efforts to address our infrastructure and housing needs.

Alongside this substantial rise in employment, the number of job vacancies has also surged, from just 500 in 2021 to 2,600 in 2025. The sharp increase in vacancies highlights ongoing challenges construction firms are facing in sourcing candidates with the appropriate skills and experience.

As the sector strives to scale up activity, the skills gap is becoming increasingly apparent. We need to address these shortages through targeted training, apprenticeships and recruitment initiatives to sustain sectoral growth and meet Ireland’s ambitious development targets as set out in the revised National Development Plan 2025.

Construction-related apprenticeship numbers have remained stable since their post-COVID-19 increase.

Figure 8 shows that annual construction apprenticeship registrations have stayed flat at around 4,500 to 5,000 over the past five years. While demand for skilled workers is rising due to Ireland’s infrastructure and housing needs, apprenticeship supply isn’t keeping up.

Immigration is another important source of skilled labour. Migrant participation in the sector (including EEA/UK workers) has grown in recent years, with the number of migrant construction workers nearly doubling from 2021 to 2023. However, recent data shows that the number of work permits issued to non-EEA/UK construction workers has not increased significantly since 2022.

Section 4 Fiscal Outlook

The data shows that Ireland’s fiscal position is robust, but concern over vulnerabilities is mounting.

The country recorded an exchequer surplus of €12.8 billion in 2024 (€1.8 billion excluding the proceeds of the CJEU ruling). This performance has been sustained by surging tax receipts amid a strong post-pandemic economy.

We expect budget surpluses to continue in the near term, with the Government’s Summer Economic Statement projecting surplus balances this year and next. However, officials, commentators and fiscal watchdog caution that Ireland’s fiscal strength is underpinned in large part by volatile corporation tax receipts, which represents a significant risk. Nevertheless, tax receipts continue to grow. Tax revenues amounted to €49.5bn in the first half of the year, up 10.5% on the same period last year (6.7% excluding windfalls).

Figure 9. Government current and capital expenditure by year

Source: DPEIPSRD

While tax revenues continue to grow, expenditure is growing also (up €38bn since 2019).

As Figure 9 shows, expenditure has grown dramatically since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Current expenditure has grown by €30bn since 2019, while capital expenditure has grown by almost €8bn over the same period. These ever-greater spending commitments would make any adjustment very challenging, were revenues to decline.

Ireland’s large infrastructure deficit leaves little room to cut capital spending if we are to remain competitive. Rainy day funds provide some protection, but the Central Bank has noted that it is “important that policy supports rigorous expenditure control — not least of current expenditure — and enables the enforcement of sustainable increases in net government expenditure over time”.

Figure 10 shows the voted expenditure across the five highest spending government departments over the last three years. Voted health spending has increased by €3.5bn in just two years. Furthermore, the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (IFAC) has noted that total spending in 2025 is growing 3.5% faster than forecast with health and education among the major drivers.

Figure 10. Voted expenditure across the five highest spending departments by year

Source: DPEIPSRD

Section 5 Topic in Focus: Ireland’s Economic Competitiveness

Global competitiveness rankings point to Ireland losing its edge.

Nonetheless, concern has been growing that Ireland’s competitiveness is under threat. In the past three decades, Ireland has transformed into a highly competitive, export-driven economy. Ireland is the seventh most competitive economy out of a sample of 69 worldwide, according to the IMD World Competitiveness Ranking 2025, but has fallen from second place just two years ago. As Figure 11 shows, there has been considerable variability in Ireland’s placing over the past five years, which may in part reflect the sensitivity of the relative ranking to minor changes in inputs.

The stakes are too high for complacency, however, as many of the fundamental factors that influence competitiveness take time to respond. Waiting to observe certain evidence of a loss of competitiveness in the data is not a winning strategy — we must remain focused on driving economic competitiveness.

Figure 11. Ireland's competitiveness rankings over time

Source: IMD World Competitiveness Ranking

Ireland’s success is underpinned by strong performance in trade and foreign investment, combined with a young, talented workforce. However, to maintain our competitive edge, we must address structural challenges, especially in upgrading infrastructure and boosting innovation capacity, that could otherwise constrain future growth.

Robert Costello, Partner at PwC Ireland.Figure 12. Housing completions vs. targets by year

Source: CSO, Housing 4 All, Rebuilding Ireland

A strong focus on competitiveness is needed to ensure Ireland’s ongoing prosperity.

Our economy is highly competitive, but this leaves no room for complacency in a world of growing uncertainty and shifting priorities. We can strengthen our position considerably by diversifying trade, attracting investment from a wider array of countries, incentivising R&D, investing in people and skills, and improving access to housing and basic infrastructure. By doing so, we’ll attract the jobs of tomorrow and continue to raise the living standards of our residents.

Section 6 Behavioural Issues

Each quarter we take the opportunity to keep our biases in check

Cognitive biases are systematic errors in the way individuals reason with the world around them due to subjective perceptions of reality. In this section, we explore the what, where, when and why of a different bias each quarter.

We are here to help you

Navigating economic uncertainties can be challenging, but you don’t have to do it alone. Our team is ready to provide expert insights and tailored solutions to help you understand and manage the complexities of the economic landscape. Contact us today to discuss any aspect of our insights and discover how we can support your business.

Sources

Bank of England, Central Bank of Ireland, Central Statistics Office, Department of Enterprise Trade and Employment, Department of Public Expenditure, Infrastructure, Public Service Reform and Digitalisation, Economic and Social Research Institute, European Central Bank, Eurostat, Federal Reserve Bank, Housing 4 All, Irish League of Credit Unions, National Treasury Management Agency, National Apprenticeship Office, PwC Global Economy Watch – Projections, Rebuilding Ireland

Contact us

Menu